Shulin Architects has completed a multifunctional service center in Liuba County, in the southwest of Shaanxi province, China. At the entrance to Liuba’s scenic mountain area and the Qinling Mountains, the service center provides a reception, public toilets, and retail facilities. With a material palette of warm wood, concrete, and natural stone, the meticulously crafted structure offers travelers and locals a place in which to stop and rest.

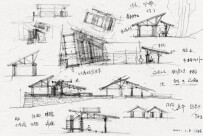

Based in Zhuantang Town, Hangzhou, Shulin Architects was founded in 2015 by architect Chen Lin. A small architectural studio, the firm places an emphasis on rural construction and traditional culture, materials and nature, the environment and people, and the relationship between old and new. Its multifunctional service center project is an example of the studio’s thoughtful and creative approach to design. In a bid to retain the memory of the original site, the service center mirrors the orientation and feel of the previous structures. "The original site has a relatively large open space and had two abandoned brick buildings,” says Lin. “We decided to design the service centre in a way that adapts to local conditions and maximizes the use of resources.”

Aerial view of the original site:

Three roofs, a roof truss, and several walls

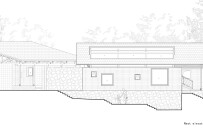

Across 380 square meters (4,090 square feet), the service center’s design is notable for its three differently-sized, single-pitch roofs with functional spaces — reception, public area, and toilets — distributed beneath.

The roofs are supported by a prefabricated plywood truss built at different scales, according to the needs of the space. “The design of the roofs was derived from traditional wooden structures in Chinese architecture,” explains Lin. “Traditional wooden structures in Shaanxi are generally simple frame structures made using small pieces of wood, as large timber was often reserved for wealthier households. We therefore decided to use smaller pieces of laminated wood to showcase the beauty of wooden structures. While the construction method and design logic behind laminated wood are typically Western, we aimed to infuse it with an Eastern sensibility by deliberately referencing traditional wooden construction dimensions. This resulted in a more lightweight structure.”

Reception roof:

Open public space roof:

Public toilet roof:

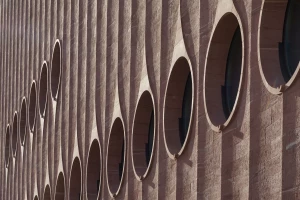

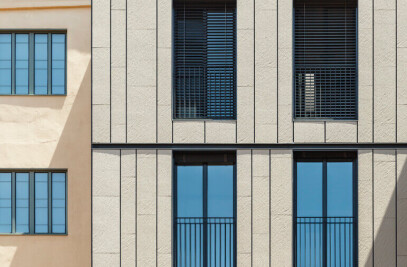

From Lin’s perspective, “the design logic of the service centre is relatively straightforward” — it has a wooden structure and roofs, and walls made from several distinct materials, including concrete, glass brick, and stone, that work to divide the center’s functional aspects. “Concrete is employed for the longitudinal walls, glass bricks are used for the short-span walls and door frames, and stone is featured in a diagonal wall within the building,” explains Lin. The service center’s warm, upper wooden half sets off its predominantly grey lower half — even the glass brick is mixed with a little grey. The contrast offers a pleasing combination of attractive and utilitarian design, emphasizing the building’s material qualities.

Materials and spatial logic

Shulin Architects envisioned a clear structural logic for the service center’s design, with the platform, walls, wooden structure, stairs, and roof coalescing as one coherent body. “Materials and spatial logic were considered simultaneously from the outset, with materials a key consideration in the initial design phase,” says Lin. The majority of materials are locally sourced, however Lin does not discount the use of materials sourced from abroad: “If all materials had to be local, both the construction and design processes would be greatly restricted,” he says. “Douglas fir and red cedar shingles are imported from abroad, the old slate (for outdoor paving) is from Zhejiang, the water millstone (for steps) is local to Hanzhong, and the stone is locally sourced.”

Better than expected?

Concrete walls were cast on-site using bamboo formwork (creating beautifully textured, striated finishes), yet Lin was initially displeased with the result. “Cast-in-place concrete has a strong degree of uncertainty — it is a one-time process,” he says. “While small-scale testing produced good results, issues arose when working on large wall areas. There were problems with seepage in the window openings, inadequate grouting at the windowsills, and many missing or misaligned sections. The bamboo formwork itself was not perfectly aligned, causing the concrete to protrude, resembling sawtooth edges. Additionally, many areas had formwork explosions, resulting in uneven wall surfaces. However, reworking the wall areas would have caused delays in the construction schedule and led to new problems. Patching them up would have resulted in inconsistent colors. The walls therefore remained unchanged.” As the construction work progressed, with the addition of the wooden framework and roofs, glasswork, and masonry rubble wall, “that rough feeling of the bamboo formwork concrete turned out even better,” says Lin.

Lin notes other occasions, during the construction process, when the reality of working with certain materials and details sometimes turned out differently than expected: “Originally, we planned to use more regular-shaped stone blocks, however their high cost exceeded the budget. As a result, we switched to using local rough stones [arguably imbuing the service center with a more traditional and warmer sense of character]. In the initial plan, we designed bamboo railings for the guardrails, but during construction opted for lighter iron railings that blended with the grey background — on-site conditions often differ from the impressions made by blueprints and models and quick adjustments during the construction process were necessary in terms of achieving the best finish.”

“Real construction”

For Shulin Architects, the design and build of the multifunctional service center was a testament to the concept of “real construction” — a “constant pursuit for our firm,” says Lin. “The idea was to clearly present and express, without any decoration, the entire process of construction — stones that slowly pile up, concrete walls cast on-site, wooden structures built on-site, old stone slabs paved one after another, and glass bricks laid one by one. For me, the biggest achievement is to provide a clear expression for the architecture.”

The service center’s design features an oblique masonry rubble wall that interweaves between the three roofs and connects into the reception’s interior. Wooden columns in the reception area are on the inside of the cast-in-place concrete wall, at a distance of 400 millimeters from the wall axis. In the public toilet, the structure is separated from the concrete wall and wooden columns are on the outside. The concrete wall and wooden structure in the open public space are connected on the same axis. For Lin, “these relations bring more fun to the space, exploring the most basic elements of the building and the organizational logic between the structure and the wall.” He continues: “Such organizational methods have been used in traditional residential construction with clear relations in each system.”

Inspired by classical gardens

Lin’s design for the service center was inspired by the Classical Gardens of Suzhou. “Classical gardens have had a profound impact on me,” he says. “They encapsulate the essence of traditional Chinese culture. Eastern cultures tend to be subtle, preferring to create intrigue, meandering paths, and hidden spaces. We often get lost while exploring gardens, something that sparks a strong interest in the space — you naturally want to discover your favorite path.” A number of paths, slopes, and stairways within the building offer visitors the opportunity to explore. One path in particular leads the wanderer to an overhead platform, with a view to the Qinling Mountains.

“Fun”

For Lin, his design is imbued with a sense of “fun", found in a mix of material and subconscious elements — the idea of playfulness, for example, is something that comes about once the functional requirements of a space are met. “While construction is a precise process, there should be moments of relaxation introduced during the design phase — it’s about striking the right balance and achieving a harmonious outcome,” he says. The service center’s design offers a range of perspectives through its interwoven walls and roofs, placement of doors and windows, and use of public spaces and pathways. “Sensory perception is particularly important — we often say that something doesn't feel right, but what exactly is the right feeling?” asks Lin. “For me, materials, texture, light, and shadow are all crucial elements that determine whether a building can captivate people. During the design process, I repeatedly scrutinize these architectural details, weighing the pros and cons to achieve what I consider the right balance.”

Lin’s keen focus on materiality and sensory perception has resulted in a building that places elements of Chinese culture and tradition within a contemporary frame.