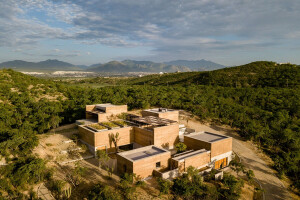

SO-IL has completed a 2,000 square meter (21,000 square foot) arts campus sited on three blocks in its hometown of Brooklyn, New York. The facility is a collection of simple volumes clad with raw materials in keeping with the neighborhood’s industrial aesthetic. Two of its buildings make use of exterior masonry walls with blocks set in atypical configurations, generating rich and innovative textures that call special attention to the otherwise commonplace brick construction.

The Amant campus is situated within East Williamsburg’s sea of low-rise truck body shops, metal cutting warehouses and fabrication facilities that have been part of this borough for the better part of a century. Garage doors, nondescript walls and bands of factory-style windows line the majority of its streets.

When the local studio SO-IL was asked to design a cultural facility combining existing with new buildings here, it wanted to respond with an architecture that would be both contextual and experimental. “It didn't make sense to design a glass storefront as one might for a gallery in Chelsea or the Lower East Side. We wanted to use durable materials, but in a way that’s surprising,” says Kevin Lamyuktseung, a senior associate at SO-IL. Concrete, brick and aluminum were selected and detailed to give new sense to the everyday. SO-IL sought to use these with a tactility that makes passersby curious to touch them. “They have a level of detail that you only appreciate up close,” says Lamyuktseung.

Amant is programmed with a mix of private and public functions: artist studios, galleries, offices, storage and a cafe. Pockets of outdoor spaces, multiple entries, and openings physically and visually connect the arts organization with its surrounding community. Public pedestrian routes with courtyards weave through and between existing buildings and offer new circulation patterns through the city block.

Masonry block production

Clay bricks are produced in various forms in nearly every American city. They are inexpensive and used in all construction types, from residential buildings to schools and industrial warehouses. The ubiquity of bricks goes hand in hand with that of masons - there is a wealth of bricklayers that can set walls, and most do so according to longstanding norms and bond patterns.

Bricks are formed by extruding low-moisture clay through a die under pressure. In construction, bricks are bound together by a cementitious or lime mortar and walls can be structural or perform as a veneer, in which case they are tied back to a substructure and separated from the building by an air gap. An architect can specify bricks of varying colors and finishes with ranges that differ among manufacturers. One common characteristic of extruded brick is the holes that run through the center, meant to lighten the brick and speed up the drying process.

To make a concrete masonry unit (CMU) aggregates such as sand and crushed stone are mixed with cement and water, formed into a mold and compacted with vibration, then removed and heated in kilns, and cured over a period of about a day. A CMU mixture will have a higher ratio of sand to gravel and water than concrete in general construction, in order to produce a dry, stiff block with high compressive strength.

Detailing the brickwork for Amant

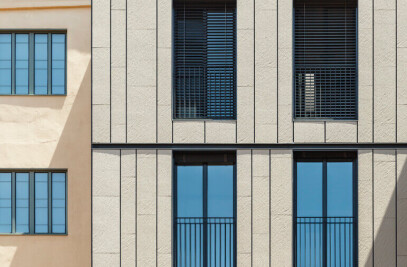

Two of Amant’s three buildings bear exterior masonry walls that challenge the standard use of blocks to yield interesting visual patterns. The first building was a retrofit, whereby an existing stone cutting shop was converted to house gallery spaces, a café and a bookstore. The exterior is clad in an inverted and scored clay brick by ACME.

When bricks of this type are extruded through machines during the fabrication process for some manufacturers, explains Lamyuktseung, rails on the machine create vertical score lines, which are not typically visible once installed. “We thought it would be interesting to use this back face of the brick to eliminate the typical running bond graphic,” he says. The resulting envelope appears as if it were carefully clad in mosaic tiles - the heavily-grained building face sheds the linear aesthetic of typical running bond in lieu of a dense sea of small bricks. “It just so happened that this brick that we found has a strike joint that is almost the same dimension as the mortar joint. It was kind of a happy accident.” This effect renders the building into a solid volume.

Within the portal of an entry corridor, the bricks transition to a stack bond with the smooth face of the masonry made visible. “The tricky part was, of course, how to turn the corner,” says Lamyuktseung. SO-IL developed a detail where the faces of the corner brick on one wall are cut according to the thickness of the score joints on the other. A viewer sees a brick of only partial depth at the merger. This detail was applied at the sides of all building openings. At the tops of openings, the use of typical exposed metal header plates was avoided to further emphasize the building as a simple, solid volume. Hidden behind the simplicity are at least a few complex details: at the underside of an an opening in an exterior wall, for instance, a hidden HSS channel supports the weight of the wall above; and it is combined with an anchor channel under which smooth-faced bricks are threaded with a rod and hung.

Amant’s second masonry building is a volume 22 feet in height and features CMU blocks by Nitterhouse Masonry. This is topped by a band of exterior aluminum louvers which diffuses daylight into a gallery space. On this building the bricks are set at an angle and, rotating out of plane to catch a shadow according to a pattern Lamyuktseung describes as ‘dogtooth’.

“When you use such a dogtooth layout around a building, it means that every single brick is set in the exact same angle of orientation,” he says. The design team worked with the contractors to produce mockups and test the joints and layout. It was necessary to allow some tolerance in the quarter inch (six millimeter) joints, yet the architects focused on achieving precise uniformity at the most visible part of the walls: the top and bottom courses of CMU, as well as at the building corners. It was especially critical to correctly and cleanly construct the corners, in order to successfully merge adjoining walls and make the building once again appear as a solid volume.

“It’s somewhat easy to do the dogtooth pattern on different building faces,” says Lamyuktseung. “You can rotate the pattern, or flip it. But somewhere on the building, corners will result with the short side of the brick from one face and the long side of the brick from the other.” Here the architects doubled the brick at the long side to create a corner condition that resonated with the others.

Another detail of the design important to the architects was giving each facade a unique tactility. The bricks are produced with two rough faces and two smooth faces, and SO-IL asked the contractors to install every brick according to the same cardinal direction. The team specified that the two rough faces of every brick in the facade face southeast and northeast, and the two smooth faces face southwest and northwest. “Each facade is slightly different in terms of the visible faces of the brick: smooth, rough-rough, rough-smooth. When you're close up, each one has a very different quality,” says Lamyuktseung. Ensuring the bricks were laid according to orientation was the most exacting point requested of the contractors. “What was important was knowing when to be demanding and knowing when to be forgiving,” he says. “Even though we dimensioned and drew every single brick, the question of tolerances meant having to figure out certain solutions on site.” Door openings, for instance, did not land perfectly at the ends of aligning bricks as intended. “So we just had to say, ‘Ok, what's the best way to make do with where we landed?’ And then we went back to the office and redrew it for record, so that we would all know what was happening.”

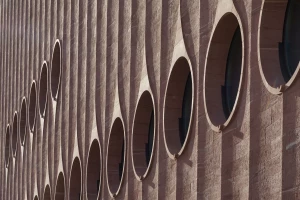

Subtle experiments with textures extended to other parts of the project as well. The third building features a structure of cast-in-place concrete that made use of form liners to produce a vertical corrugation. Many of the concrete floors were raked while still fluid to form wave-like patterns that a visitor can feel with their feet. Elsewhere in the project, semi-open galvanized steel channels line the exterior walls at street level to once again emphasize verticality.