The International Rugby Experience is an ambitious cultural project by London-based Níall McLaughlin Architects, built to honor the worldwide game of rugby. Located in the Irish city of Limerick (considered “the spiritual home of rugby”), the project embodies the ability of sport and architecture to revitalize a community.

Níall McLaughlin Architects places a firm emphasis on the inventive use of building materials, and on the importance of the relationship between a building and its surroundings. These factors were pertinent to the planning and development of the International Rugby Experience, a project that was constructed over five years and completed in 2022. From the exterior, the 7-story building is unlike a typical experience museum. There is no immediate wow factor and therein lies its appeal. Built on a tight urban site, the predominantly brick building has a sober physicality. At its front, a tall tower, crowned with a double-height glass gallery, is set back from the street by a portico. A lower block that connects with the tower matches the height of surrounding Georgian buildings.

In a conversation with Tom McGlynn, the project architect and an associate at Níall McLaughlin Architects, he discusses the International Rugby Experience’s design and materiality. Offering a view on the building’s function as a modern-day sports museum, McGlynn explains: “From the client’s perspective, it should be something active, present, and exciting, more than simply a series of memorabilia. While the client worked on finding an experience design agency, our focus was very much on providing a building to accommodate the experience-based brief.”

A historically sensitive setting

The building sits on the edge of a conservation area within Limerick’s Georgian Quarter. Placing contemporary architecture within sensitive sites is part of the bread and butter of Níall McLaughlin Architects. “The setting is historically sensitive, particularly from a conservational viewpoint,” says McGlynn, “however, it’s in a position in the city center where the historic grain has gradually been eroded along the main shopping street.” The client settled on the given site because of its prominent location and the International Rugby Experience’s potential to become the driver in Limerick’s social, physical, and economic regeneration.

A decision was made that the building’s design should be civic in nature. The ensuing planning process was complex and involved consultation with heritage groups. The architectural proposals were based on research into Georgian era buildings. “We were looking at historic buildings that break the monotony of the four-story townhouse terrace,” explains McGlynn. “These tended to be churches or town halls, many of which unashamedly rise above the houses that surround them, celebrating their public purpose and civic presence. From an architectural perspective, that was the narrative for us.”

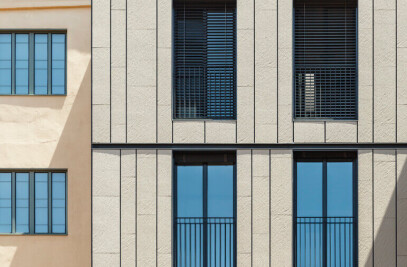

Red brick was chosen because of its fit with the vernacular of Limerick’s Georgian Quarter. In the articulation of the facade, “we considered a vertical rhythm that chimes with the abutting Georgian terrace,” says McGlynn. “We were careful in terms of how we would situate the building, tying it in with the Georgian part of the city.”

Designing the International Rugby Experience

As a building, the International Rugby Experience stands tall, with an unashamed church-like or town hall-like quality. It has a commanding presence and a wonderful, albeit restrained, elegance. McGlynn explains the reasoning behind this: “It comes from the brief and what is required internally. With an emphasis on a digitally-focused, multi-sensory experience, there was a challenge to reconcile the architecture with the need for black-box spaces. Two of these spaces are located behind the blank facade of the tower. We were keen to give the facade a sense of expression, breaking down its mass by adding vertical brick fins. This establishes a grid that allows a series of openings and blank walls.” The brick fins are a pleasing design feature, encouraging the interplay between light and shadow. Where the building turns the corner from its position on O’Connell Street onto Cecil Street, there are more windows on that facade and a continuation of the rhythmic brick fins. “It is a reference to those historic buildings — church architecture and civic architecture — that elevate their facades above a standard blank wall,” says McGlynn.

In the building’s design, structural forces that are expressed through the architecture reflect some of those forces found within the game of rugby. McGlynn explains: “The fins are seen to support the top of the building with those expressive arches and columns. Our aim is to help people understand the building’s structural forces. The client was in favor of the architecture being a key part of the experience, so in the black-box rooms, for example, the brickwork and ceiling vaults are visible. There is an awareness of the architecture, of the building and its materiality, and the idea that the experience sits within this context as an installation.”

As a practice, Níall McLaughlin Architects will make a case for natural lighting and views from a building wherever possible. “I would say a successful part of the design of this building is the journey through the space, which is predominantly a vertical one,” says McGlynn. “Where openings and windows are positioned, they allow a reorientation back to the city. The floors beneath the top floor are black-box spaces. There is an enjoyable episodic moment as you pass through these spaces and emerge on the top floor, where you find your sense of light and views heightened.”

Brickwork and vaults

The International Rugby Experience was conceived as a brick building from an early stage of the project. Initially, a hand-laid brick building was a possibility, however concerns about finding appropriate contractors, the program schedule, and cost, led the architects to working with precast concrete panels instead. Brick is used throughout the structure, on its facade and pillars, floors and walls. With a traditional-meets-contemporary quality, the brickwork has a warm, visual, and tactile appearance.

“We considered a number of brick types and chose a handmade brick from Charnwood, a brick manufacturer in Loughborough, UK,” says McGlynn. “It is quite a small outfit and we visited them to look at various blends of red brick, settling on three different reds from their standard range — they can be mixed and thus achieve more depth.” McGlynn describes how the brick is used: “One of the main reasons we decided on the Charnwood brick was because it has a ‘frog’ in the middle of it; when the brick is cut in half, there is a jagged back edge which is good for our facade. The brick is fixed to precast concrete panels and the jagged back edge is used to key it in. As the brick is made by hand, we also get four fair faces — visual faces — to the brick, meaning that for every brick made, we effectively get two bricks. By using each half on the facade, there is an obvious efficiency as well.”

The vaulted ceilings, with their reddish hue to match the brickwork, are a notable addition to the building’s overall design. They have the appearance of a monolithic structure made with concrete, but in actuality they’re not. “The entire building is a steel frame structure and we initially thought about using prefabricated vaults made of glass reinforced plaster, but the costs were prohibitive,” explains McGlynn. “The main contractor then elected to make the vaults from bent plasterboard — the plasterboard is scored and folded around a metal frame to create the form. The concrete vaulting would have had carbon footprint issues as well as loading issues, and so we finished up with a more lightweight ceiling. The key benefit has been the ability to use an acoustic plaster. It has a concrete-like appearance and will acoustically temper each space.”

A crowning moment

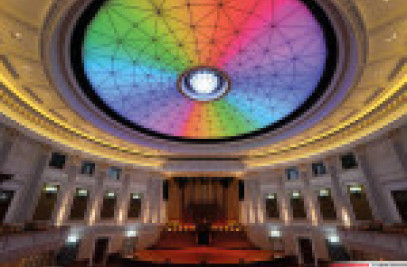

The gallery’s design came about during the planning consultation, when sensitivity around the building’s height was expressed by concerned parties. “It was agreed that the top of the solid brick part of the tower could match the height of the large bank building opposite,” says McGlynn. “The top floor gallery would then be light and as see-through as possible. We know that transparency is impacted by reflections and how modern glass is treated. A way to counter this is to bring light in from above, meaning the glass is essentially backlit and becomes more transparent. The principle around bringing in roof light led us to think about the architectural form of a vaulted ceiling.”

The resulting vaulted ceiling in the upper gallery is captivating in its sculptural formation and volume. The studio arrived at its shape following a lot of three-dimensional studies, hand-sketching, and modeling. McGlynn describes the vault as “eye-shaped” or almost “rugby ball-shaped” and explains the complexity of translating this into a form that could be built: “The vault was constructed in a very traditional way. There’s a timber formwork behind the ceiling which is like the hull of a boat; the plasterboard is scored and bent around this, with plastering over the top to unite the whole thing. A crash deck was built high up in the space, meaning the builders were working in a fairly constrained area, cutting plasterboard strips and plastering the ceiling. It was definitely a labor of love and is one of the features the builders are most proud of. It’s very much a crowning piece at the top of the International Rugby Experience building.

International Rugby Experience brick specials

International Rugby Experience floor plans