ATTA-Atelier Tsuyoshi Tane Architects has completed a thatch-covered building with a footprint of 15 square meters for the Vitra campus in Weil am Rhein, Germany. The project is the result of an intense study of vernacular architecture and a proposal for the future of sustainable design.

Tsuyoshi Tane, founder of ATTA, visited the Vitra campus in Weil am Rhein, Germany last week. He was there for the opening of the exhibition ‘Tsuyoshi Tane: The Garden House’ at the Vitra Design Museum Gallery, which is dedicated to the recently constructed Tane Garden House, a thatch-covered building that combines a rooftop viewing platform for campus visitors and a meeting room for the gardeners who tend the grounds. The house serves a garden completed in 2020 by the Dutch landscape architect Piet Oudolf and is an excellent addition to an already astounding collection of architectural jewels on the campus designed by industry titans that include Frank Gehry, Tadao Ando and Zaha Hadid.

The Garden House is set at the heart of the Vitra campus and is among its smaller-scale interventions. “The project was very special both for me personally and for the atelier,” says Tane, whose Paris-based studio is located on a rooftop of a former parking garage in the city’s 12th arrondissement. “I visited the Vitra campus when I was a student and I was very much in awe. So it was an honor for me to be included here and at the same time very stressful to be a part of something with these master architects.”

Rolf Fehlbaum, Chairman Emeritus of Vitra, invited Tane to Weil am Rhein in 2020, and asked him if he would like to work on a new sort of project for the campus. “Vitra was becoming concerned about the issue of climate change, that architecture and design should somehow take this into account on the campus,” says Tane. “Rolf wanted a garden house that could symbolize the idea of sustainability. It is a big subject for such a small project to talk about.”

For three years Tane and Fehlbaum deliberated over this idea. Tane’s project, completed in the spring of 2023, boasts an exquisite attention to detail that aims at rewriting the way architecture might be practiced to embody sustainability. It is a subtle construction that is also heavily researched. And for a site and client with such global reach, the Garden House found a way to be surprisingly ‘local’ in its aims.

‘Archaeology of the Future’

Tane’s atelier houses hundreds, if not thousands, of small models that are studies in raw material and form. These sorts of models accompany all of the studio’s projects, which currently include the master plan for a three-kilometer public park, and a forthcoming building for the Imperial Tokyo Hotel. “We use our hands and work with physical models. It is important to make everything more human in scale,” he says. Modeling is at once creative and scientific. And it is as much a process of making as it is one of extraction: through repetition and testing, core concepts can be discovered, distilled and refined.

Much about the way Tane describes architecture is scientific and methodic. He uses the term ‘Archaeology of the Future’ as a summary for his approach. “I am fascinated by the work of archaeologists. They go to a place, often in the middle of nowhere, start digging in the ground, and can discover objects of a site from hundreds or thousands of years ago, and sometimes this kind of discovery can change history,” he says. “That gives me a lot of inspiration.” Each project site, so to say, can be an opportunity to offer something from history that has been lost to the present.

“Modernism used to be a strong driving force for creating the future and changing the world completely, but in the 21st century we are seeing all these city developments and new highrises where the global construction industry takes over cultural heritage. Somehow it is getting uncomfortable. We see the same kinds of cities everywhere,” he says.

According to Tane’s theory an architect’s job is to manifest buildings that connect a site’s memory with its future. In this way architecture can find specificity so as to avoid the generic. This is the ideology he has applied to many of his projects and one that evolved in his approach to the Garden House as he sought a novel response to questions of sustainability in the context of the German countryside.

Focusing on the vernacular

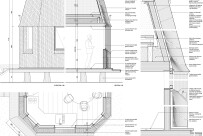

The Tane Garden House is compact and intended to accommodate up to eight people. It takes a form that is octagonal in plan and with a roof that is slightly canted. The small interior space is equipped with a coffee area and a workshop area, and the building is used to store tools used by the caretakers of the garden and workers that tend to its bees. The project features outdoor seating and a small fountain for watering or cleaning boots and utensils. It is topped by a platform from which offers visitors 360-degree views of the campus.

The form and design of the house is the result of a lengthy set of studies based on needs and values rather than a response to a specific project brief. “When we started there was no clear timeline,” says Tane. “There was constant discussion with Rolf, proposing then getting comments, like ping-pong, back and forth.”

“We started our research in an archaeological way,” says Tane, doing so by going back to the human origins of the garden. “The garden symbolizes the beginning of our capturing nature to heal the body, for growing food and medicine. In this way the garden is not so natural, but a man-made collection of species that we gather and take care of.” Living with gardens compelled humans to construct habitations in response to this specific way of life. “There is a vernacular in living this way. Houses were built in relation to their natural environments,” says Tane, referring to the various typologies that differ based on geography, from the dry African deserts to wet Asian climates. “People woke up and took water, found wood, fed animals, cooked and washed while living in nature. There was a process, and I learned that the houses adapted to the process.”

Tane studied the vernacular of Swiss houses constructed in the Alps starting from around the 15th century. These varied based on village and site as well as the knowhow of local people and the building materials that were available to them. “In the details there are many beautiful techniques that were passed down over generations,” he says. “These are the houses passed from grandmothers to grandchildren, with modifications made continuously according to the people that lived in them.” At the invitation of Fehlbaum, Tane also visited the famed Ballenberg Swiss Open-Air Museum, a site that displays over 100 traditional buildings transported from around Switzerland, prompting the design team to further uncover the role of village life as it relates to sustainability.

Designing a home in thatch and rope

Two parallel themes were at play as the project for the Garden House advanced: that of sustainability and that of craft. Tane and Fehlbaum focused on creating a prototype of sorts using natural materials and, more importantly, local building techniques. The team sought regional craftsmen that would be brought on board to inform the design based on individual building methods, a challenge in that the architect would be learning from, say, available stonemasons and ropers, rather than hired consultants. The project would also be constructed without a general contractor.

The Black Forest in southwest Germany, near the Vitra campus, is dense in greenery. Homes in the region traditionally used thatch grown in the forest for protection. Tane did his research and found that the best regional thatch produced today is actually from Austria, from where it could be delivered to the site by train and car. Thatching is a technique that involves the layering of dried plant stalks to insulate a building and shed water away from its roof, and the Garden House is enveloped in thatch installed by young Austrians that were inheritors of the craft.

The story is similar for the majority of the materials selected for the project. “We looked for the closest craftsmen we could find,” says Tane. The handrail leading to the roof, for instance, was installed with rope instead of using metal. “We found a roper living in Basel, a magician from a family of many generations of ropers.” Eight ropes were tied in a way that is visually simple but technically complex, to achieve great tension.

An octagonal form

At a moment when he believed Tane’s team was being too formalistic in its general approach to the Garden House, Fehlbaum explained to Tane that the industrial designer Charles Eames designed seats and legs as individual objects before designing attachments, which was done only through a process of trial and error. “There was a struggle to find a design process like that of Eames’,” says Tane.

Tane and his team decomposed the project into its various elements - a foundation, a staircase, a roof - before putting them back together. “We began with a simple square in plan, and then we started chopping off corners to allow the sun to enter as it runs around the planet over 365 days,” he says. “We wanted to celebrate solar movement as well as the ability to see into the fields everyday over the different seasons, like in vernacular homes.”

The beveled corners also allow for effective cross ventilation as the winds change course. “It was a simple idea for the sun and wind to be part of the design process, where all of these small details welcome the wind or sun in different seasons to be ventilating or illuminating according to different orientations.”

In section, a unique, curved edge detail was developed at the connection point between the octagonal walls and the roof, which are all thatched surfaces. The slight curvature allows the water to slide off the roof without draining down the walls.

Material choice: staying ‘above ground’

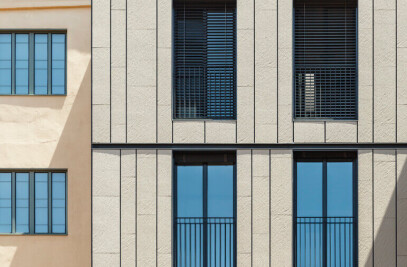

Today’s architecture, according to Tane, plays a significant role in climate change for its reliance on the extraction of underground resources. To counter this he followed the concept of ‘above ground ’ for the Garden House, sourcing materials such as stone, wood, thatch and rope. The granite used in the house traveled some 28 kilometers from the quarry to the stonemason and finally to the site, while the wood traveled a total of 50 kilometers from the Black Forest to the factory and then the campus.

The idea of treading lightly and using less resources also applied to the construction process by employing local workers. Working locally in this way is important for the long term care of a project, according to Tane. “Modern buildings, once finished, are often hard to carry on,” he says.” We cannot sustain many buildings done in an industrial way,” such as buildings constructed in Spain using materials imported from China. “We can construct them but we cannot fix or repair them because you cannot deliver exactly the same material 50 years later. The machines change and the material life spans are short.”

“Of course we cannot compete with the stones of cathedrals, but here at Vitra every ten or twenty years when the thatch will need to be replaced, people from here will participate in doing that,” says Tane. Such a way of building and thinking lets people celebrate architecture as a part of society, as well as helps them to see that there is dialogue between the planet and our buildings.

It is clear to Tane that the rigorous design process implemented to realize the Garden House helped it to achieve its ambition of being both modern and vernacular. “Someone told me that he can't tell how old it is,” says Tane, proudly, of the house. “It is supposed to be the latest project on campus but it looks like it has been there a long time.”