For the reconstruction of the town hall of Voorst, in the forested countryside of eastern Netherlands, architecture office De Twee Snoeken developed a hempcrete facade made from the stalks of regionally harvested plants. It’s among the largest applications of the biobased material in the region.

It is perhaps obvious that a municipal building should be constructed from regional materials. But, for many reasons, it is too rarely the case. When the city of Voorst, the Netherlands, issued an invitation to tender for the demolition and reconstruction of its existing city hall built in the 1980s, it required that the new project be a landmark of sustainability. De Twee Snoeken, a local Dutch firm, won the project and developed it with an innovative envelope harvested from regionally grown hemp. The project’s envelope thus bears a positive and direct relationship with the land.

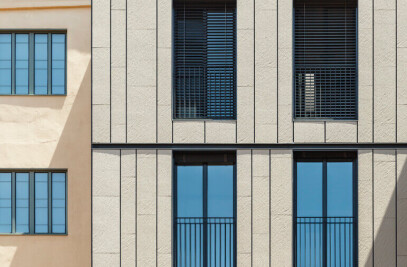

“The environment where the building stands has really beautiful surroundings and a great natural environment,” says Joost Roefs, the project architect. “The municipality said they didn’t want an extreme, showy building. The people of Voorst are really down to earth, so we wanted the building to be something special without showing off.”

Roefs and his team were responsible for contracting all the trades for the project, so they had the freedom to choose where to invest in innovation. Focus was placed on the materiality of the envelope. Roefs believed a simple but richly layered material could give the building the unique and natural identity it needed.

Rammed earth was initially considered for the project for its warm and earthy texture. But rammed earth walls are typically thick and loadbearing, and one of the municipality’s requirements for the project was to maintain the structure of the existing building. Rammed earth is also not an inherently isolating material.

Hempcrete, on the other hand, has a similar layered texture to rammed earth while having the additional characteristic of being insulating. It is not used in a load-bearing manner and so could yield walls of only 38mm in thickness for the building in Voorst, giving additional space to the interior program. It became the natural choice.

Hemp is carbon-negative, recyclable and biodegradable. It has a low embodied energy and does not yield polluting byproducts. It can be grown without the use of pesticides and can help to regenerate depleted soil. Unlike concrete, which emits large amounts of CO2 during production, hemp absorbs CO2 back from the atmosphere. During the growing period, it is estimated that one hectare of hemp can absorb about 15 tons of CO2 from the atmosphere. For the facade in Voorst, 13 hectares of hemp were planted in nearby Groningen and harvested after four months, consuming some 200 tons of CO2.

Hemp is resistant to fire and mold. It is a lightweight and porous material which ‘breathes’ to allow the regulation of air and moisture; its porosity also gives it the characteristic of being insulating and acoustic for more comfortable interior working conditions. For all these reasons, it can have the effect of reducing a building’s long-term energy consumption and result in a net-positive return for the environment.

Hempcrete production: basic, but not easy

The use of hemp for fabrication is not novel. It has been used for many years for manufacturing industrial products like rope and textiles. But the use of hemp in building construction has often been limited by costs and, depending on the location, a lack of supply. It has also been limited by building code: hemp was only recently approved for use in housing in the United States, for example.

Walls can be constructed of hempcrete using relatively elementary means, poured into molds like traditional concrete, as a combination of hemp fibers, lime and a chemical binder or water. But pouring hempcrete on-site is also labor-intensive; in the case of Voorst it necessitated being poured and compacted by hand. Constructing a hempcrete facade, consequently, requires some level of experience and technique.

Despite this, according to a market analysis by Roefs, in the context of Voorst where access to nearby agricultural land for growing hemp was ample, the cost of a hempcrete facade was estimated to be similar to that of a quality brickwork.

Prefabricated blocks versus casting in-situ

One method of producing hempcrete walls is to manufacture them as blocks or panels in a factory. There are a few reasons for this: construction schedules are often tight, so casting a hempcrete wall on site might not be possible; second, hempcrete requires certain weather conditions and might not dry adequately in periods of frost or inclement weather. Finally, forming a wall on site can lead to cracking or other unexpected defaults.

Prefabricated blocks can be joined on site to form walls. This eliminates the need for and costs associated with formwork. One aesthetic challenge, though, is then joining these blocks to achieve homogeneity as well as benefit from the wall performing as a sealed shell. Joints can always be filled and colored, but the finished product will not achieve the same visual uniformity as a hempcrete wall cast and rammed in-situ.

Modularity and Formwork

Like concrete, hempcrete is a liquid mix that is poured into formwork. Based on the design of the mold and the size of particles in the mix, hempcrete can be used to form complicated shapes, with integrated supports, piping and window frames, though it must be beveled at the corners to avoid chipping and cracking at weak points. Roefs’ team tested various hemp strand sizes in the mix to achieve the building’s smooth, marbled texture.

When poured in-situ hempcrete is compacted in layers to give a wall its clean linearity. Roefs sought to make a homogeneous facade uninterrupted by joints and so required that a typical module be the full height of the two-storey building at 7 meters. The length was set at 15m to align with the structural grid. And the mold was given a scalloped shape as a reference to the design of the earlier structuralist-style building. “We wanted to show the existing structure and the way the architects used the exterior walls to create a rhythm and to downscale the building,” says Roefs. The resulting curvature yields shadows which accentuate the envelope’s inherited cadence.

Roefs required that each full-height module be completed in a single day. “We had 15 people standing in a row pouring the hempcrete in and putting pressure on by hand in layers,” he says. This method helped to guarantee visual consistency across each surface of the hempcrete.

Hempcrete’s layered nature and lengthy drying period makes it prone to cracking. At Voorst the team encountered more fissures than anticipated. “We had some bad nights without a lot of sleep until we figured out what was happening,” says Roefs. The problem was determined to be only aesthetic. “The cracking has since stopped, but it shows this was really a pilot project.” The superficial cracks were filled with a hempcrete of smaller particles and protected with the same colored sealant, once dry. In case of future damage the same repair process will be followed.

A Breathing Material

The envelope performs as a seamless, airtight and windproof shell. There is also, in the case of Voorst, no need for additional waterproofing. In fact, the wall can technically be constructed without any buildup, insulation or finishes and still ensure a comfortable indoor climate. “For an architect it’s like a dream material,” says Roefs. Elements like window frames can be embedded within the hempcrete without the need for additional flanges or thermal breaks. And due to its insulative properties the 38cm facade built in Voorst yields an Rc value of 5.7 m2 K/W.

Roefs chose to add a 2cm permeable stucco with a chalk base on the interior to ensure a clean interior surface. “What's important for the interior finish is that it also breathes,” says Roefs. “Because the hempcrete breathes by itself, it takes on water and this is really good for your interior atmosphere, but then you have to use a finish which does the same, otherwise it would stop hempcrete from breathing on the inside.”

Foundation and Roof Detailing

Though hempcrete walls are strong, the material is porous and needs to be protected from prolonged exposure to water. The interface between an exterior hempcrete wall and both the roof and ground is critical to ensuring there are no long-term erosion issues. In base detailing, the main goal is to prevent capillary action from rising damp. Another concern is the exposure to water splash at the intersection of horizontal and vertical planes. This also applies to window sills and other projections.

To protect the top of the wall from water exposure at Voorst a 70cm roof overhang was designed around the perimeter of the building. And where the wall comes into contact with the ground, it is set on a 25cm brick plinth to protect the hempcrete portion from rising humidity and splashes. The hempcrete slightly overhangs the base; here a drip cap is integrated into the design. At the windows, a precast sill with a drip edge is used.

Because of the techniques required to achieve high-quality finishes and long-term protection against sunlight, cast hempcrete has typically been finished in a supplementary material, such as stucco. In only a few built examples in the Netherlands, according to Roefs, was hempcrete expressed as a raw material. But these buildings were small and required protective sealants to be reapplied every three or four years, a procedure that was not economically viable for a large-scale municipal building. Roefs needed to find a longer-term solution that could guarantee the quality of the facade over the coming decades.

He settled on working with a Dutch firm that produces mineral paints for brickwork, locally referred to as keim, to design a custom sealant that would protect the facade with the necessary level of resilience for a decade or more. For Roefs, it was important that the natural hemp color and marbled texture was expressed. “We asked for an entirely transparent mix but they had to put in some color to block the UV radiation,” he says. “We decided to make a mix that was 50% transparent and 50% color with a tone to reflect the natural color of the hempcrete.” This mineral paint was applied several months after the hempcrete dried, and requires reapplication every 10 years.

The result is a one-of-a-kind finish that achieves an outstanding degree of warmth, comfort and homogeneity. Furthermore, the color of the facade reflects that of the hemp plant, as a direct expression of the regional material.

Further references:

Allin, Steve (2012). Building with hemp. Seed Press.

Stanwix, William; Sparrow, Alex (2014). The Hempcrete Book: Designing and Building with Hemp-Lime. Cambridge: Green Books.